Latest government policies on homelessness, child poverty and more offer little help to migrants

In the last few weeks of 2025, there was a raft of government policy announcements on migration, housing and homelessness. But good news was limited, and many measures look harmful. Starting with the new homelessness strategy, we take a look at the government’s proposals and their impact on migrants.

The national plan to ‘end homelessness’

On 11 December, the government published its long-promised homelessness strategy, A National Plan to End Homelessness. CIH’s overall response was welcoming but called for the government to go further.

The 90-page document has only one short section (3.4.6) on ‘Refugees and migrant homelessness’. It recognises that people leaving the asylum system represent the second biggest group of those sleeping rough after “leaving a public institution”.

It proposes:

- Ensuring councils receive information from asylum accommodation providers for 100 per cent of newly granted refugees at risk of homelessness within two days of a notice to end support, or within 14 days of issuing a family reunion visa

- Various administrative improvements to ensure that the promised notice periods work in practice

- Ensuring refugees receive “early, targeted support to integrate through advice and guidance on securing onward housing and employment”

- Delivering long-term reform to create an asylum system that “works for both new refugees and the communities they become part of” — but with the promise here referring specifically to ‘large sites’, including former barracks.

A later section notes that the government is working with councils to develop more locally led accommodation models, including through Afghan resettlement pilots and the new £500 million fund for a more sustainable model of asylum accommodation.

On migrant rough sleeping, the strategy only offers:

- Funding a ‘homeless migrants capability training package’ for councils and voluntary sector organisations

- A pilot in four council areas on access to immigration advice, short-term accommodation and a named point of contact within the Home Office to support councils to help people sleeping rough with restricted or unknown eligibility for public funds.

It also reiterates the availability of voluntary returns to home countries as a route out of homelessness.

However, there is nothing on the length of the move-on period from asylum accommodation, despite repeated advice from the sector that this is crucial to preventing homelessness among those granted status. The strategy ignores barriers refugees face to accessing private rented accommodation and has no targeted extra funding for prevention beyond the two limited schemes dealing with rough sleeping.

Comments on the homelessness strategy include ones from CIH and NACCOM.

Government issues child poverty strategy

The government’s child poverty strategy, published in December, was broadly welcomed, but many groups pointed out that it would still leave many migrant children in poverty. While the Refugee and Migrant Children’s Consortium welcomed the recognition of the experiences of children with no recourse to public funds (NRPF) in the strategy, it noted the context of wide-ranging asylum and immigration plans announced by the Home Office that could keep children across the immigration system on short-term visas with NRPF for decades, with penalties of 15 and 20-year routes for families who access the support they need for their children. The asylum plans include a consultation in 2026 on reduced rights to public funds for recognised refugees.

The Children’s Society pointed out that there are few concrete measures in the strategy to tackle child poverty caused by NRPF conditions. Praxis said the strategy leaves thousands of migrant children — 40 per cent of all children in poverty — “out in the cold”. The Conversation argued that, to truly tackle child poverty, the UK “needs to look again at migration policy” because of NRPF conditions which are believed to cover some 578,954 children and which will affect them for longer if planned policy changes go ahead. A follow-up story explored the effects on children in more detail.

In 2019, Project 17 produced Not Seen, Not Heard, a report on children’s experiences of NRPF. Six years later, estimates suggest that around 382,000 children affected by the NRPF immigration condition in the UK are living in poverty, a new briefing shows. United Impact, a solidarity-action group supported by Project 17, has made an animation to show the extremely harmful impact of NRPF on families in the UK.

The Guardian told the story of this mother of a disabled child who cancelled her benefits because of fears it would lengthen the amount of time she has to wait before applying for settlement. Free Movement points out that government plans include any past history of claiming benefits while in the route to settlement, “so stopping now will not necessarily benefit people unless transitional provisions are put in place.”

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation published a study on the effects of NRPF on families in August.

The government’s violence against women and girls (VAWG) strategy

The government’s new VAWG strategy was published on 18 December. But although it acknowledged the vulnerability of asylum seekers to domestic abuse, it was light on new proposals.

There will be a requirement for police to seek a domestic abuse victim’s consent before sharing their information with Immigration Enforcement. The strategy’s action plan includes a promise of better processes “to identify risk in the asylum estate and improving the support offer and response to migrant victims”.

However, whilst the strategy is clear in acknowledging the barriers that migrants, asylum-seeking and refugee women face, CIH believes there is insufficient investment in specialist services or legal reforms that will support these women in escaping abuse.

CIH welcomes the step to limit data sharing to ensure that migrant victims can report their experiences to the police and only have immigration authorities notified with their permission, a call it has long supported. But this step will need to be accompanied by visible publicity, as perpetrators are likely to continue to use threats relating to immigration status. In their response, Southall Black Sisters said the changes do not represent a true firewall to encourage migrant survivors to come forward.

A shortcoming of both the VAWG Strategy and the recent plan to end homelessness is the failure to address NRPF, which leaves victim-survivors more at risk of both abuse and homelessness.

CIH’s response to the VAWG strategy can be seen here.

Two major immigration reform policies announced in November

Not longer after publication of the Autumn newsletter, the government made two big announcements on migration policy:

- On 17 November, the home secretary’s policy paper, Restoring Order and Control: A Statement on the Government’s Asylum and Returns Policy, outlined measures to reduce arrivals, strengthen enforcement and expand safe and legal routes. Here are the initial comments from the CIH, Refugee Council and Refugee Action.

- On 20 November, the home secretary published A Fairer Pathway to Settlement, which proposes replacing the automatic five-year route with an earned settlement system based on a 10-year qualifying period. The consultation on the proposals is open until 12 February.

This newsletter has a detailed article by Marie-Anne Fishwick of ASAP, explaining what we understand the policies to mean for asylum support. Other excellent briefings and commentaries on the proposals that came out in the run-up to Christmas are:

- The West Midlands Strategic Migration Partnership’s briefing note on the policy paper and another on the Fairer Pathway consultation.

- Free Movement’s detailed briefing on the implications of the ‘earned settlement’ proposals and what they might mean in practice. Jon Featonby says 160,000 refugees granted settlement in the last five years now face a 15-year wait, even though they were months away from ILR.

- Women for Refugee Women set out seven ways in which the asylum proposals would harm female asylum seekers.

- Personal comments on the government’s proposals by people with experience of the asylum system appeared in Big Issue and the Guardian.

- The Conversation said that Britain should think twice before following Denmark’s example in its treatment of asylum seekers. The Guardian took a similar view.

- Colin Yeo argued in We Wanted Workers that “you can’t promote immigrant integration by making it harder”.

- Munya Radzi from Regularise, which coordinates the Migrant Workers’ Rights Coalition, called the government plans “the hostile environment on steroids”.

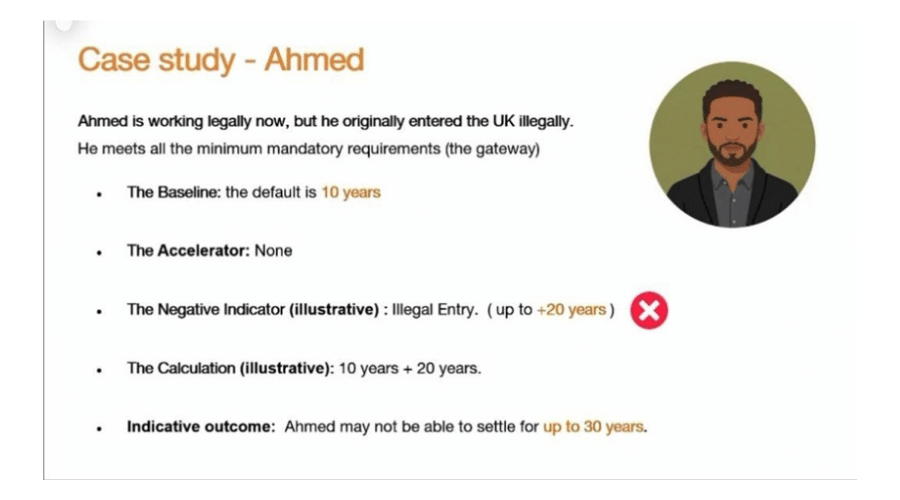

- Slides from a Home Office presentation for employers on “earned settlement” were posted on Bluesky. The case studies explicitly play the ‘good migrant’ versus ‘bad migrant’ narrative. ‘Ahmed’ (see slides) may have to wait 30 years.

- Shaheen Syedain, who works for Freedom from Torture, warns of the impact that Labour’s sweeping changes to the asylum system will have, by making family reunion much more difficult.

- Together with Refugees has a video in which community groups come together to tell the Home Office “We choose compassion not cruelty”.

- “Asylum is not illegal migration — why the UK government shouldn’t conflate the two”: The Conversation makes the case for more careful language.

- UK in a Changing Europe outlines the effects on the asylum appeals system.

- The Migration Observatory addresses the top 10 problems in the evidence base for public debate and policy-making on immigration in the UK in 2025. Among these is the lack of good information on the impact of migration on public services.

Meanwhile, the Home Affairs Committee has an ongoing inquiry into routes to settlement. The House of Lords Justice and Home Affairs Committee has also launched an inquiry into the process of obtaining indefinite leave and British citizenship and invites written evidence by 23 January.

Presumably part of its publicity for the coming changes, the government has launched a new TikTok that shows videos of people being handcuffed, bundled into police cars and frogmarched into detention centres.

Expert views from Colin Yeo and Zoe Gardner

The London Review of Books has an excellent, wide-ranging podcast with Nicola Kelly, solicitor Colin Yeo and James Butler discussing the government’s proposals and the political context. Colin makes the point that the new proposals focus on changing conditions for migrants who are here (or arrive in future), rather than on reducing numbers by cutting visa opportunities (for example). They have the effect of making it more difficult for people to “settle in as soon as possible”.

A new report from migration expert Zoe Gardner was welcomed by Labour backbenchers. Published by the UK-based campaign group Another Europe Is Possible, Time for change: the evidence-based policies that can actually fix the immigration system is seen as a sensible and pragmatic alternative to the government’s current immigration policy proposals.

Gardner argues that the government has become mired in a no-win situation. Its approach to immigration has been disappointing. It is failing both migrants and the needs of British communities. The alternative approach outlined in the report starts from the recognition that the UK needs immigration to sustain growth and fund public services in an ageing society.

Statistical footnote — are government policies working?

In January it emerged that, in defiance of government policies, small-boat arrivals were 13 per cent higher, at 41,472, in 2025. This is the highest figure since 2022.

However, net migration is now assessed to have fallen drastically to just 204,000 in the year to June 2025, down 80 per cent from its peak in 2023. Nevertheless, polls show that people think it is still rising.

The government expects new measures during 2026 will further reduce net migration by around 100,000 from current levels; in contrast, the chair of the Migration Advisory Committee argues that it will rise again to around 300,000 by 2030. An alternative suggestion that government restrictions could bring net migration down to zero, which would see the UK’s population stagnate, seems implausible, however.

Also, in the year ending June 2025, just 16 per cent of UK immigration was accounted for by asylum seekers and refugees. This was made up of around 96,000 asylum seekers, 17,000 Ukrainians and 7,000 other people resettled because of conflicts abroad, and 21,000 family members of refugees given visas to enter the UK.